Eating more sweet food may not sway sweet preference

Randomized controlled trial shows that eating more — or less — sweet-tasting foods didn’t change how much people liked sweet flavors

Turns out, your sweet tooth may not be shaped by your diet. Findings from a new randomized controlled trial suggest that eating more sweet-tasting foods doesn’t increase someone’s preference for sweet tastes.

A new study found that after six months on diets with varying amounts of sweet foods, study participants' preference for sweetness stayed the same, no matter how much sweet foods they ate. Additionally, consuming a lower or higher dietary sweetness did not affect energy consumption or body weight.

Eva Čad and Leoné Pretorius

The researchers found that after six months on diets with varying amounts of sweet foods, study participants' preference for sweetness stayed the same, no matter how much sweet-tasting foods they ate.

“We also found that diets with lower or higher dietary sweetness were not associated with changes in energy consumption or body weight,” said the study’s lead investigator, Kees de Graaf, PhD, emeritus professor in sensory science and eating behavior at the Division of Human Nutrition and Health at Wageningen University in The Netherlands. “Even though many people believe that sweet foods promote higher energy intake, our study showed that sweetness alone isn’t to blame for taking in too many calories.”

Eva Čad, a doctoral fellow at Wageningen University, will present the findings at NUTRITION 2025, the flagship annual meeting of the American Society for Nutrition held May 31–June 3 in Orlando.

“Most studies examining the effects of repeated exposure to sweet taste on the liking, or preference, for sweetness have been short-term, covering periods up to one day,” said de Graaf. “Without consistent data on the longer-term effects, the basic question of whether or not sweetness preferences are modifiable has been unanswered.”

To address this research gap, the investigators conducted a study based on a validated approach to measuring sweet taste preferences using foods and drinks developed especially for the trial and not administered as part of the intervention diets. The rigorous design followed a pre-registered and ethics-approved protocol with strict adherence throughout the trial.

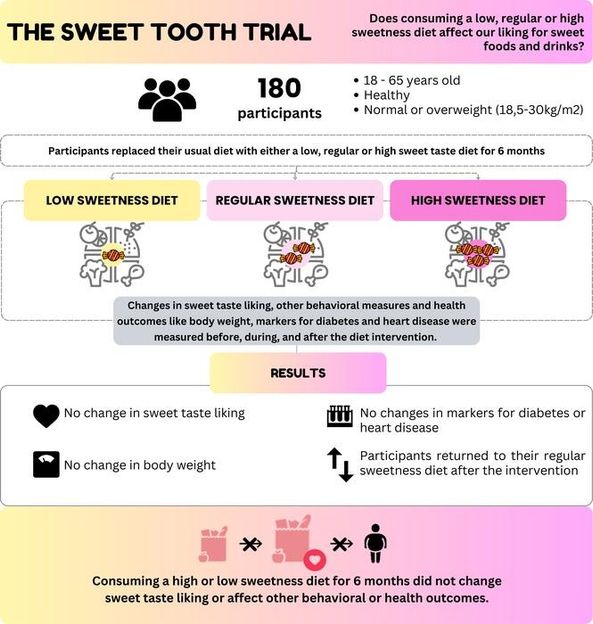

For the study, three groups of about 60 volunteers—180 participants total—were each given diets with mostly sweet, less sweet or a mix of foods. This was done by delivering food and drink packages every two weeks for six months, providing about half of each participant’s daily food items. The study participants received daily menus for guidance but could eat as much or as little of the provided foods as they wanted.

The researchers categorized foods based on their sweetness using data from their previous study that measured taste intensity in about 500 commonly eaten Dutch foods. Sweet products included items like jam, milk chocolate, sweetened dairy and sugar-sweetened drinks. Non-sweet items included foods like ham, cheese, peanut butter, humus, salted popcorn and sparkling water.

Each person’s preference for sweet taste was tested before the intervention diet began, two times during the diet, directly after the diet ended, and one and four months after people were no longer following the assigned diet. The investigators also looked at total energy and macronutrient intake, dietary intakes during the trial and physiological measures like body weight, body composition and blood markers for the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases, such as glucose, insulin and cholesterol.

To make sure that there were no confounding factors, the carbohydrates, fat and protein composition of the foods and drinks provided to each group were matched. They also randomized people with similar sex, age and body weight to avoid large differences among the groups.

The researchers found that lower exposure to sweet-tasting foods did not lead to shifts in sweet taste preferences, changes in sweet taste perception, changes in food choice or energy intake. Likewise, the group eating more sweet-tasting foods did not experience an increased preference for sweet foods. They also found no association between the amount of sweet foods consumed with changes in body weight or biomarkers for diabetes and cardiovascular disease. After the intervention, the participants naturally returned to baseline levels of sweet food intake at the 1- and 4-month follow-ups.

“This is one of the first studies to measure and adjust sweetness across the whole diet within a realistic range of what people actually consume,” said de Graaf. “This matters because some people avoid sweet-tasting foods, believing that regular exposure will increase their preference for sweetness — but our results show that’s not the case.”

Next, the researchers would like to repeat the study with children, a group that may still be flexible in forming their taste preferences and eating habits.