Delicious at last: New proteins to revolutionize gluten-free baked goods

In the near future, bread could also come from the 3D printer

Advertisement

Daisies, peas, rapeseed & Co.: Researchers at the University of Hohenheim want to replace gluten protein with new alternatives. Instead of ovens, 3-D printers would be possible.

Gluten is one of the largest natural proteins and has fantastic properties: It keeps a well-cooked dough airy until baking stabilizes the open-pored structure. Prof. Dr. Mario Jekle of the University of Hohenheim in Stuttgart is working on processes in which selected proteins from peas, rapeseed, rice or corn, for example, directly replace the gluten protein, or can be linked together to form chains with gluten-like properties. Saponins from daisies and quinoa seeds or so-called mucilages from grain hulls additionally support the structure of an airy dough - and in some cases enrich it with valuable dietary fiber. The result can go into the oven - or be printed out in the 3-D printer in an energy-saving way and with many additional options.

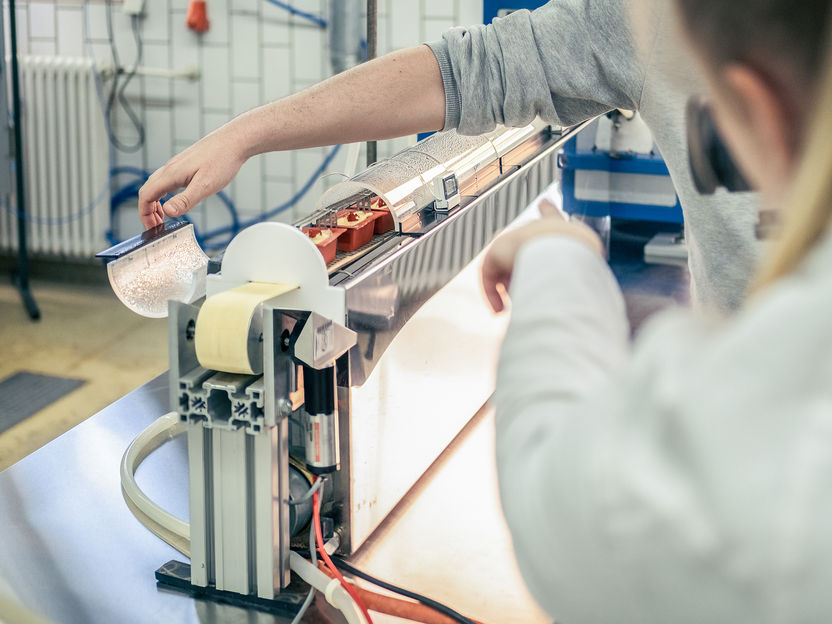

The rolls that are currently coming off the production line at the Food Science Technology Center are still small. The pastries, which Natalie Feller portions onto the hand-width conveyor belt in small silicone box molds each containing 30 grams of dough, are just about the size of a model train car.

The mini rolls are steamed with moisture for a good two meters. This is followed by another two meters in the continuous baking oven. At the end of the mini-baking line, the test buns emerge golden and steaming.

Feller is a doctoral student in the Department of Plant-based Foods at the University of Hohenheim. Her goal for the day is to make the baked goods as fluffy as possible. To achieve this, she has swapped the laboratory for the pilot plant. Here, the food scientists at the University of Hohenheim have at their disposal, among other things, a complete range of equipment, such as that used in the bakery trade, dairies or butcher stores.

Daisies, peas, rapeseed & Co.: In these mini test loaves, alternative proteins give the dough a fluffy, airy structure that can otherwise only be achieved with gluten

Universität Hohenheim / Oliver Reuther

Gluten proves to be a problem protein in around 2 to 3% of the population

Feller's baking experiment combines many things: food technology with materials science and engineering. The special challenge in this experiment is the recipe: the dough is completely gluten-free and yet is supposed to produce fluffy and tasty baked goods.

The reason: in two to three percent of the population, gluten proves to be a problem protein: "We now know of three clinical pictures that are related to gluten," reports Prof. Dr. med. Stephan Bischoff from the Institute of Nutritional Medicine at the University of Hohenheim.

The best known is celiac disease, a mixture of allergy and autoimmune disease. Wheat allergy, which is triggered by gluten and similar peptides, is similarly widespread. In addition, there is wheat sensitivity, which is the third disease pattern and has been the least researched to date. "It is not yet clear what exactly triggers wheat sensitivity and whether gluten also plays a role in this case. That is why we are working intensively on this mystery in our department."

Patients suffering from celiac disease in particular have only one remedy in everyday life: to resort to gluten-free foods.

Gluten serves as a supporting structure in classic baked goods

In chemical-physical terms, however, gluten is a highly exciting protein, finds Prof. Dr. Mario Jekle, head of the Department of Plant Foods. "Gluten is not only one of the largest known proteins in the world. It has outstanding properties in baking," says the food scientist.

In fact, he said, you can think of a fully proofed dough as a kind of foam that solidifies during baking. The protein gluten gives this foam structure and supports it so that it doesn't collapse prematurely.

That's exactly where many gluten-free baked goods fall short: Getting the ingredients to "foam up" is not a problem. This can be achieved by stirring or using yeast, baking powder and other leavening agents, just as with classic wheat flour dough. "What has hardly succeeded so far is keeping the many small gas bubbles in the dough without the supporting gluten framework."

Protein chains made from natural proteins should provide a remedy

With their current research, the food researchers at the University of Hohenheim are therefore taking a new approach: "Instead of supporting the dough with gluten, we are concentrating on stabilizing the interface between the gas bubbles and the dough with alternative proteins," says Prof. Dr. Jekle.

To do this, the scientists working with the food scientist are using new, tailor-made proteins. The starting materials are natural proteins from peas or rapeseed, from which the food scientist extracts the optimal proteins.

The new protein alternatives are supported by natural saponins. These are obtained from quinoa seeds - or from the stems, leaves and flowers of daisies.

Prof. Dr. Jekle sees further potential in plant breeding: "If we define the requirements precisely, we can work with plant breeders to specifically breed new pea varieties whose proteins are even better suited to our approach."

Another approach provides additional dietary fiber

In another approach, the field is trying to chain natural proteins from rice, corn or oats with mucins, known as arabinoxylans. These mucilages are found in almost all cereal hulls, which are also used as bran or animal feed.

It is an approach with additional benefits, because in this way Prof. Dr. Jekle's working group enriches baked goods with valuable dietary fiber. Their importance is also emphasized by nutritional physician Prof. Dr. Bischoff from the University of Hohenheim. "To give one example, 30 grams of dietary fiber a day is already good prevention against colon cancer, one of the three most common types of cancer in men and women."

The food scientists at the University of Hohenheim are therefore planning to explore the use of arabinoxylans in other foods as well - for example, in meat substitutes. The exciting thing about this is that the approach not only enables substitute products with a meat-like structure, but the dietary fibers also provide them with a rather unique additional benefit. So far, there are no comparable products on the market.

In the near future, bread could also come from the 3-D printer

Another vision is to loosen the dough and bake it in a single step - with the help of 3-D printers. In this process, a nozzle builds up the pastry together with the pores in millimeter-thin layers. A baking unit is placed above this, which immediately solidifies each layer.

The process is thus somewhat similar to the way Salzwedel bakers have been baking the classic Baumkuchen for 200 years. Here, too, the dough is applied in millimeter-thin layers and classically fixed over an open fire. "However, our technology at the University of Hohenheim is of course much finer, more flexible and can build up many different structures," emphasizes Prof. Dr. Jekle.

For him, the 3D printer is almost a standard piece of equipment, and he has been experimenting with it for several years. Whether it's baked goods, meat, meat substitutes or side dishes - in principle, almost any food could also be produced from the individual components in the 3D printer, he is convinced.

As a supplement to the classic kitchen, the 3D food printer also brings two other advantages: "With printed foods, I can personalize meals, i.e., align the ratio of fats, carbohydrates, proteins and all other components precisely with the individual needs of individual people. And I can also obtain some of the raw materials from residual materials that are produced during food production, for example."

Note: This article has been translated using a computer system without human intervention. LUMITOS offers these automatic translations to present a wider range of current news. Since this article has been translated with automatic translation, it is possible that it contains errors in vocabulary, syntax or grammar. The original article in German can be found here.