Global food production threatens the climate

The use of fertilisers in agriculture is primarily responsible for man-made nitrous oxide emissions

Advertisement

The concentration of nitrous oxide - also known as laughing gas - in the atmosphere is rising sharply, driving climate change. Next to CO2 and methane, it is the third most important greenhouse gas released by human activities. The use of fertilisers in agriculture is primarily responsible for man-made nitrous oxide emissions. Due to the growing demand for food and animal feed, emissions could increase in the future. This was the result of an international study published in the journal Nature, in which the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) was involved.

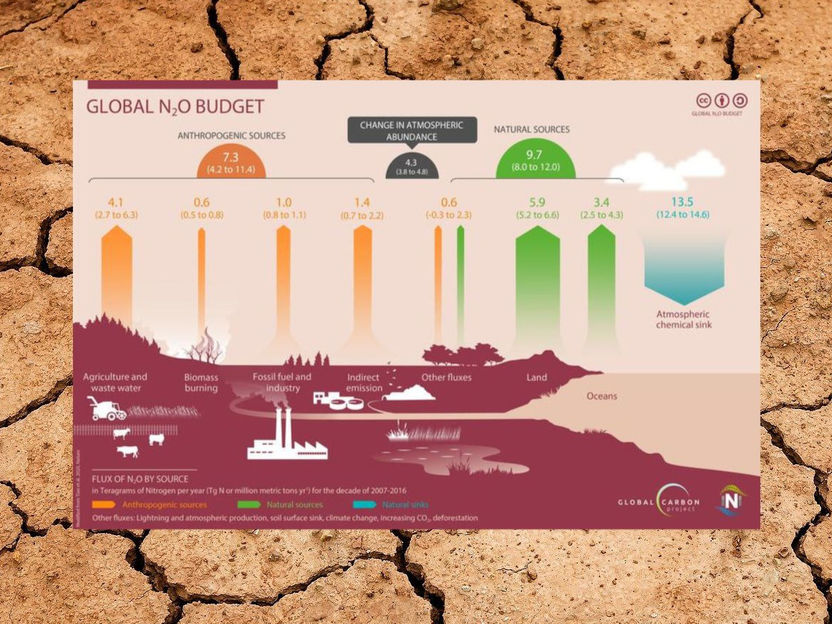

Global N2O budget for the years 2007 to 2016: Anthropogenic sources are shown in orange.

Tian et al. 2020, Nature; Global Carbon Project, International Nitrogen Initiative

Around 300 times more harmful to the climate than carbon dioxide - this is nitrous oxide (N2O), also known as laughing gas. Laughing gas remains in the atmosphere for around 120 years. Although it only occurs in trace amounts, its strong greenhouse effect means that it contributes disproportionately to man-made climate change in terms of quantity. The concentration of nitrous oxide in the atmosphere is already around 20 percent higher than pre-industrial levels. In recent decades, the increase has accelerated due to emissions from various human activities. Overall, global N2O emissions in 2016 were about ten percent higher than in the 1980s. The most comprehensive assessment of all nitrous oxide sources and sinks to date is provided by an international study led by researchers from Auburn University in Alabama/USA, which has now been published in the journal Nature under the title "A comprehensive quantification of global nitrous oxide sources and sinks". Their conclusion: In view of the sharp rise in nitrous oxide emissions, the climate objectives of the Paris Convention are at stake.

"The rise in nitrous oxide concentrations in the atmosphere is mainly due to the use of nitrogenous fertilizers. These include both synthetic fertilizers and organic fertilizers from animal excrements," explains ecosystem researcher Almut Arneth, professor at the Institute of Meteorology and Climate Research - Atmospheric Environmental Research (IMK-IFU), the Alpine Campus of the KIT in Garmisch-Partenkirchen. She participated in the study. "In the years 2007 to 2016, agricultural production caused almost 70 percent of anthropogenic global N2O emissions." Since the demand for food and feed continues to grow worldwide, the researchers fear that the global N2O concentration in the atmosphere will also continue to rise and contribute to global warming.

N2O emissions in Europe decreased

The study also shows that man-made nitrous oxide emissions are highest in East and South Asia, Africa and South America. Increases are particularly high in emerging economies, especially China, India and Brazil, where arable and livestock production has increased significantly. In Europe, by contrast, anthropogenic N2O emissions have decreased, both in agriculture and in the chemical industry. Scientists attribute this to various incentive and protection measures. In many Western European countries, for example, agriculture has switched to using nitrogen more efficiently, partly in order to reduce water pollution. "Our work provides a deeper understanding of the N2O budget and its impact on the climate," explains Arneth. "It also shows that there are ways to reduce emissions, for example through various measures in agriculture that affect both production and consumption. Such measures not only benefit the climate, but also biodiversity and human health".

A total of 57 scientists from 48 research institutes in 14 countries participated in the study "A comprehensive quantification of global nitrous oxide sources and sinks", which was headed by Professor Hanqin Tian from Auburn University. It was conducted as part of the Global Carbon Project and the International Nitrogen Initiative.

Note: This article has been translated using a computer system without human intervention. LUMITOS offers these automatic translations to present a wider range of current news. Since this article has been translated with automatic translation, it is possible that it contains errors in vocabulary, syntax or grammar. The original article in German can be found here.