How Coke still tingles after a year

Plasma coating makes food last longer

Advertisement

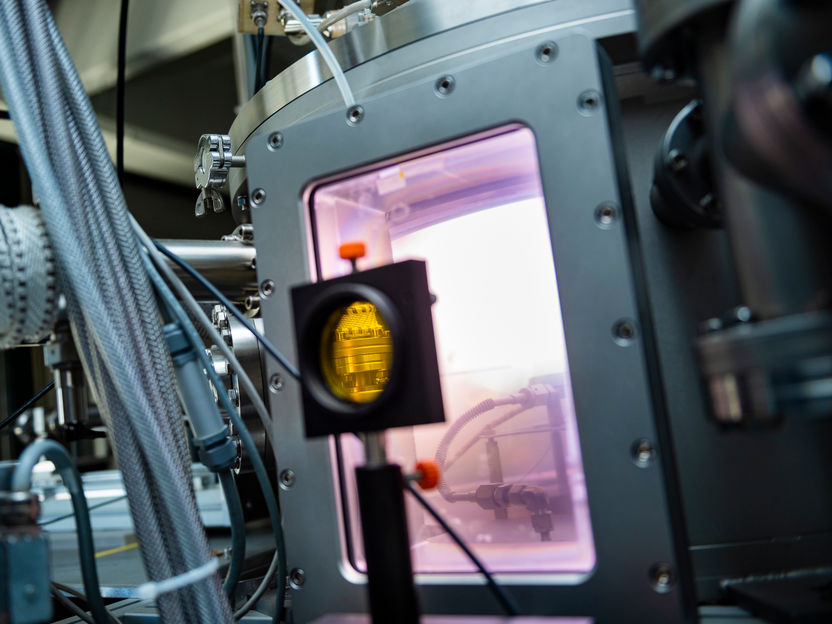

A few nanometers thin quartz-like coatings can multiply the shelf life of food, enable brilliant OLED TV images or separate gases. They can be neglected in recycling.

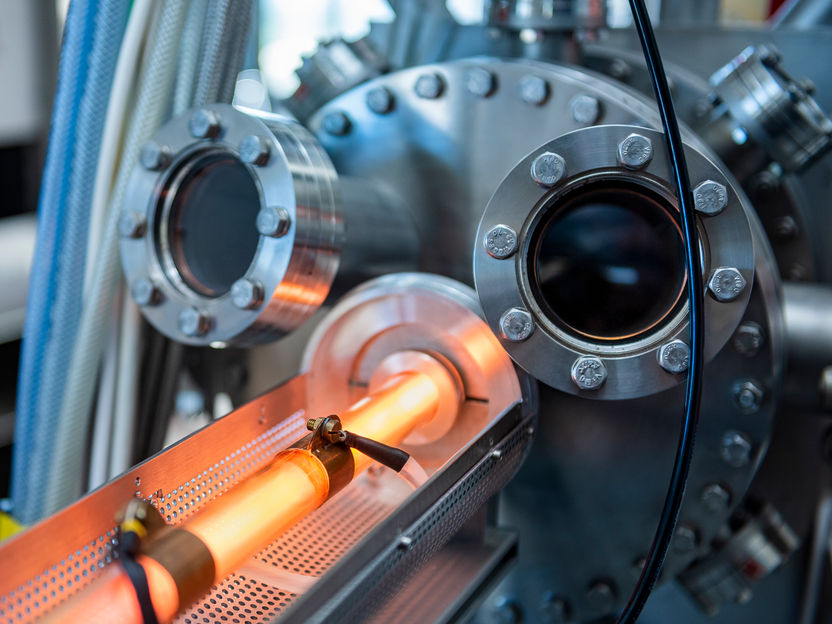

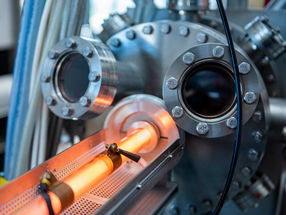

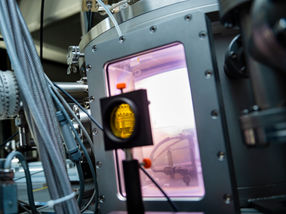

A capacitively coupled plasma (CCP) source for the generation of nanoparticles. The nanoparticles are embedded in composite layers for filter membranes to control the selectivity for different gases.

Damian Gorczany

Marc Böke (left) and Peter Awakowicz in the laboratory

Damian Gorczany

Damian Gorczany

Damian Gorczany

Damian Gorczany

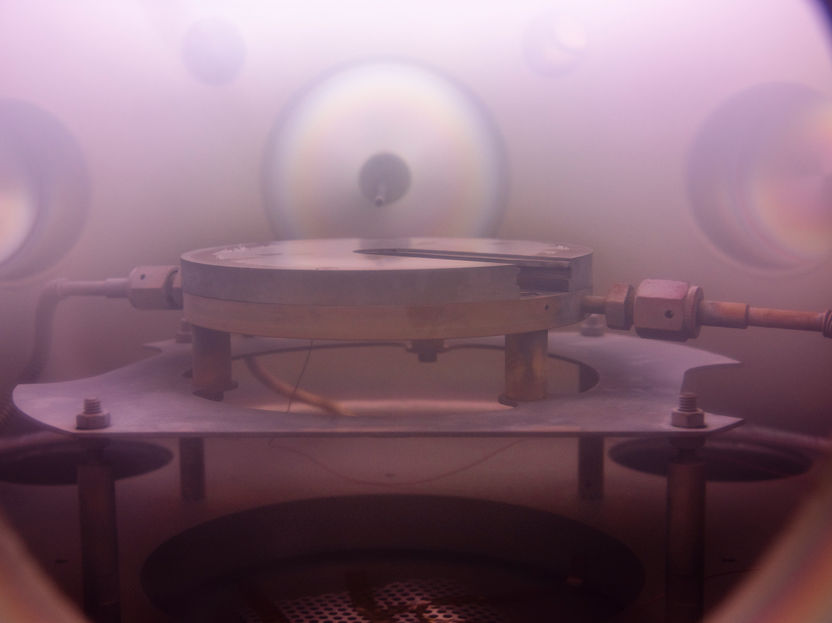

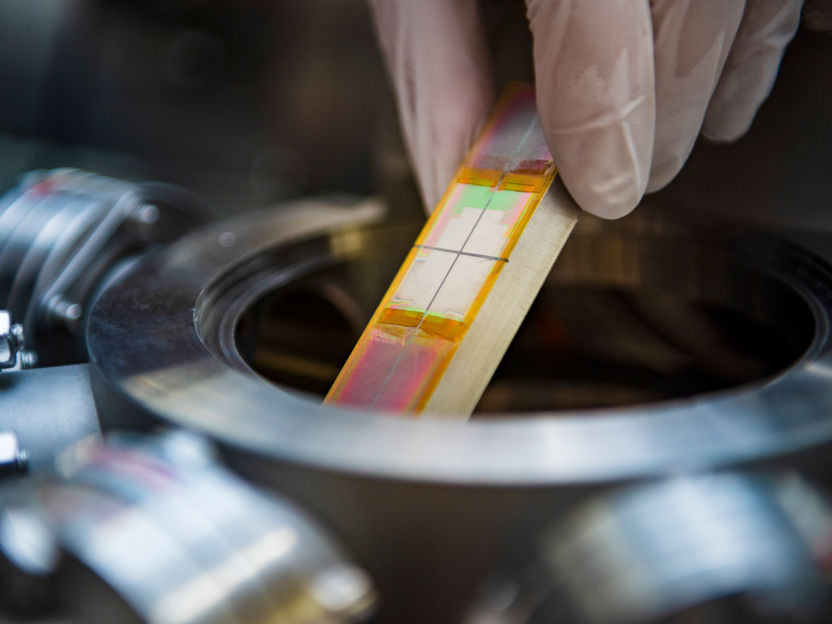

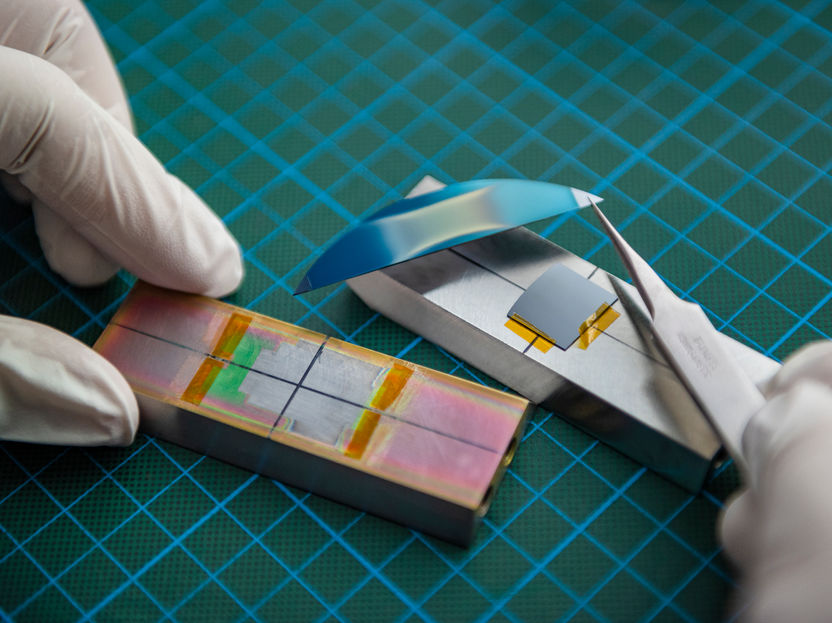

Different samples in preparation: on the left a PET film, in the middle a silicon wafer on which a silicon dioxide layer with embedded nanoparticles has been deposited, and on the right an untreated silicon wafer.

Damian Gorczany

If one specifically ensures that polymers are formed in plasmas and deposited on the surrounding surfaces, one can coat them in a targeted manner. Thanks to this so-called Plasma Enhanced Chemical Vapour Deposition, or PECVD for short, it is possible, for example, to apply extremely thin, gas-tight coatings to the inside of PET bottles, which ensure that the contents last longer, or to protect organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) from moisture so that the television screens function for a long time. Teams from the General Electrical and Plasma Engineering and Experimental Physics II departments at the Ruhr-Universität Bochum (RUB) have perfected this technique. They report in Rubin, the science magazine of the RUB.

Making milk and medicines last longer

The coating is only possible because the plasmas are cold and therefore do not damage the PET bottle or other surfaces to be coated by heat. Only the fast electrons in the plasma are hot, and they do not damage the surfaces. The glass-like coating of the plastic, which is only 20 to 30 nanometers thick, ensures that 10 to 100 times less gas escapes through the bottle. This extends the shelf life of a lemonade from four weeks to about one year. The method is also of interest for the packaging of milk and other foods, as well as medicines and even microelectronic components. "This type of coating is also environmentally friendly, because the tiny amount of material can simply be neglected during recycling," explains Dr. Marc Böke from the Experimental Physics II department.

Oxygen makes the difference

The challenge lies in controlling the formation of the layers. "The layers should not only be ultra-thin, but also absolutely dense, free of gaps and uniform," explains Marc Böke. The adjustment screws for this are manifold. For one thing, it depends on the gas mixture. Atomic oxygen is a particularly important player here. The pressure under which the plasma is operated is also important. Similarly, the geometry of the reactor and the choice of energy source affect what happens in the plasma and how it affects the surrounding surfaces. "In general, different sizes of plasma reactor are possible, up to the huge dimensions needed to coat entire window panes for high-rise buildings," said Peter Prof. Dr. Awakowicz.

Measurement techniques had to be developed

The researchers were able to gradually fathom and perfect many aspects of the possible processes. For example, PET bottles are cleaned and activated before coating, also by means of plasma. But here, too, the surface of the bottle changes, which in turn influences the subsequent coating. Measurements of the particle flows during cleaning have revealed what happens. If the process is allowed to run optimally, this has a considerable influence on the success of the subsequent coating: "We were able to increase the tightness, which was initially a factor of 100 (depending on the substrate material), to a factor of 500 by correctly adjusting the previous cleaning," says Peter Awakowicz.

The latest application that is currently being worked on makes a virtue out of necessity: If one actually wants layers that are as dense and defect-free as possible, defects such as the smallest pores in the coating are almost impossible to avoid. They allow the research teams to use plasma coating to develop non-swelling filter membranes that exhibit previously unknown properties. They can desalinate water or separate gases, such as oxygen from CO2.

Note: This article has been translated using a computer system without human intervention. LUMITOS offers these automatic translations to present a wider range of current news. Since this article has been translated with automatic translation, it is possible that it contains errors in vocabulary, syntax or grammar. The original article in German can be found here.